3 Frameworks For Making Complex Decisions

Life is full of complex decisions: capital purchases, such as a car or a house, planning a vacation, choosing a new job, picking a product strategy, prioritizing roadmaps, hiring someone. Complex decisions have several shared traits: the list of options is often extensive, evaluation criteria are ill-defined, the outcomes are hard to predict, input data is unavailable or incomplete. Humans understand large systems by building mental models, which are more straightforward than the reality they represent. Mental models are a great thing: they allow us to make progress without getting bogged down in every little detail. But they also have their flaws. Most notably, human cognitive biases, our failures to think and communicate clearly, lead us to sub-optimal decisions.

Psychologists and behavioral economists have spent a considerable amount of time and mental energy dedicated to understanding the human decision-making process. By systematically understanding our cognitive biases and flaws, smart people have come up with frameworks to counteract their ill effects. Using these frameworks can lead to decisions with better eventual outcomes., how we fail, and how to make decisions that lead to better results. Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler, Dan Ariely, and Chip Heath have done seminal research in this field — and distilled their ideas into highly readable books. Thinking Fast and Slow, Nudge, Predictably Irrational, and Decisive are amongst my favorites. I strongly encourage you to read these to gain a deeper understanding of the field.

In this post, I present three practical frameworks to improve decision- making in different contexts. Frameworks are hard to understand in the abstract. Just reading theory leads to a shallow understanding of how to apply them in practice. To make things more concrete, I use two practical problems that I have solved using some combination of these three frameworks.

- How to buy a car: Large capital purchases, such as buying a car or a house, can make for challenging decisions. Some input data for our car-buying determination: I have a growing family with small kids. I have a short commute to work. I care about style and comfort. I don’t intend to race my car on a track. I care about the environment and would like something efficient. I have a nominal budget of $50k in mind. A cursory examination of the car market should quickly reveal a broad spectrum of options. For the sake of this post, let’s narrow that down to 1) a minivan (Honda Odyssey), 2) a hybrid sedan (Prius), and 3) a pure electric (Tesla Model 3).

- How to pick the next feature: We make many complicated decisions at work. Product Managers and organizational leaders often need to decide what part of their product they should focus on given their goals. This strategic choice is perhaps the most impactful, on par with perfect execution. Input data: our app is in the market. It is growing slowly. Churn is higher than we’d like. Research shows that the current set of customers like the app, but don’t love it. Should we focus on acquiring new users, increasing lifetime value, or churning fewer users?

How Not To Decide#

1. Gut Feeling#

Listening to your gut is probably the most common approach to decision making. It’s the way we make most decisions - if we did an exhaustive process to decide what to eat for lunch, we’d never get anything done or be able to make any progress. Instinct is your subconscious brain pattern matching inputs with what it has seen in the past and making a quick, shortcut decision. Our brains are fantastic at taking in vast amounts of data and making gestalt decisions; don’t fight your instincts.

However, when it comes to highly complex decisions, the very brain that helps us make rapid decisions and move forward with life, deludes us into making bad decisions. Our fast decision-making process is often known as the “reptilian brain” or “System 1 thinking”. It is the reason we survived on the savannah: when we thought we saw a lion, our brain didn’t take its time working through whether it was a bird, or a blade of grass, or a zebra. It told us to climb the tree first. Our deep-thinking, thoughtful cousins were pruned out of the family tree by the lion. These instant reactions, fight-or-flight instincts, all the shortcuts our brains use, can show up as cognitive biases in decision-making.

Let’s use the car buying example. Imagine we walked into the local Toyota dealership. It’s a boiling hot day in the middle of summer. Salespeople are extremely busy, overworked, and slightly rude. They give us the keys to a car that’s been baking in the sun. We test drive it, hate it, and pass summary judgment: it’s a pile of rubbish. The car is way too hot, takes forever to cool down, drives like a sloth. Additionally, we’re unhappy about not being treated like royalty and don’t want to buy from that dealer anyway — hard pass.

We have attributed the rudeness of a particular salesperson to not just the entire dealership, but all the dealers of this specific car manufacturer. This mistake is called a fundamental attribution error. We have attributed the car’s inability to cool down instantly to a manufacturing flaw. We have ignored the base rate: all vehicles sitting in the sun on that day were hot and would take time to cool down. As a result of these biases, we may have discarded a perfectly reasonable option thanks to our instant decision making brain.

2. The Giant Spreadsheet#

I love spreadsheets. They allow me to organize my life (and I love organization) and view things at various levels of detail. It is very tempting to distill every decision to some formula and take the flawed human out of the loop. The formula can be straightforward: weighted sums seem to do the trick. Every decision now becomes so precise, so mathematically elegant. Don’t like the outcome? You must have gotten the inputs or weights wrong.

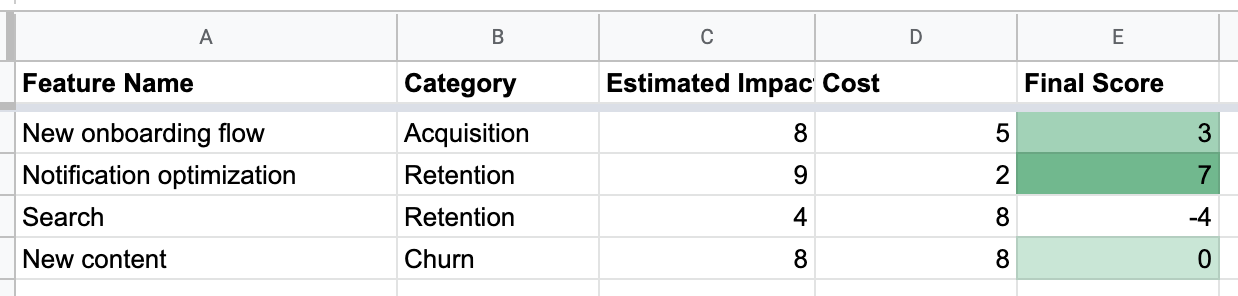

Let’s visit our product feature prioritization decision. We could build features that target acquisition, LTV, or churn. Each row has a cost and an impact estimate. Any Product Manager worth their salt will come up with a table of priorities, each of these features as rows, and drop columns to show potential impact. Some complex mathematical jiu-jitsu comes next, and the potential impact column has numbers and color coding from red to green. We must pick the greenest feature because our matrix just told us so!

This approach is problematic because it reduces humans to automatons and throws out all intuition. Moreover, it overly simplifies the model by diminishing highly complex information into a number. In the made-up example above, working on notifications seems to win over everything else, using the scheme I’ve put in. But that the model itself is biased - cost and impact estimates might be completely bogus, our gut might tell us that focusing on acquiring new users is more important, or that the cost of doing notifications is probably higher.

Intuition is essential — our brains are pattern-matching against past experiences and predicting the future. Numerical models create a false sense of precision and delude us into trusting the models. Our minds are excellent at translating vast amounts of information into decisions, and we should trust them while finding ways to correct their shortcomings.

Decision Frameworks#

The next section outlines the three decision frameworks that I have used in some shape or form. None of these frameworks are mine - I have merely adapted them for my purposes and found them to be applicable and relevant.

Framework 1: Reducing Dimensionality#

The credit for this idea goes to my friend and colleague Josh Williams. The principles are easy to understand and apply on the fly, require little formal work, and help break through a decision making logjam.

Complex decisions are often challenging because they contain an overwhelming number of dimensions. Decomposing the problem results in a large number of smaller choices along each dimension. However, dimensions are not orthogonal — changes in one affect another. Trying to optimize all dimensions at the same time quickly gets overwhelming.

Take the car-buying example: we need to make individual decisions about passenger capacity, gas mileage, styling, manufacturer, safety features, cargo hauling, maintenance, buy vs. lease, and so on. In the example above, we need a car that can carry five humans, is efficient, stylish, safe, easy to maintain, and costs less than 50k. A Porsche 911 is stylish and safe, but doesn’t cost less than 50k or carry five humans. A minivan fits most of the requirements but is on the lowest end of the style spectrum. A Prius is in the “meh” range on most things but does excellent on efficiency. The perfect car simply doesn’t exist. What do we do?

A good approach in such circumstances is to reduce dimensionality. If you magically cared only about your budget and passenger capacity, the answer would become much more apparent. We can reduce dimensionality in 3 ways:

- Aggressively ignore dimensions that you don’t care about. In the car example, we could stop caring about maintenance. Maintenance plans are straight forward. Almost every major manufacturer has a good policy. Let’s get rid of that completely.

- Create “threshold” dimensions that you care about up to a certain point, but not beyond. For example, safety matters to my family, with our small children. But beyond a specific safety rating, any car is sufficiently safe, and we don’t need to optimize any further.

- Establish trade budgets. This is not dimension reduction per se, but helpful in understanding the relationships between different things. For example, if we care more about efficiency than style, and getting a high gas mileage is worth twice as much as having a sexier car. This approach gives us a rough calculator to prioritize the dimensions we genuinely care about.

The beauty of this framework is that you can quickly sort through the dimensions that matter and devalue or completely discard the ones that don’t. Moreover, when we end up with a few real choices at the end of the process, we are assured that all of them satisfy our constraints and would make us happy. Beyond this point, all decisions are good decisions.

Framework 2: Mediating Assessments Protocol (MAP)#

This approach is from an excellent article by Daniel Kahneman, Dan Lovallo, and Olivier Sibony. If this summary piques your interest, I encourage you to read the article in full. It is clear, easily understandable, and practical. If you’re at a tech company, such as Google or Facebook, and are using a structured interviewing process, you’re already using MAP without knowing about it.

Remember the “giant spreadsheet” approach to making decisions? The problem with that approach was that it threw out all human intuition. What if we kept an element of intuition in the mix, but had a way to neutralize a variety of cognitive biases? This is the central idea behind the MAP framework proposed by Kahneman and team.

Let’s revisit the feature prioritization problem. We need to make a decision on which feature to build next. There is a trap here — we can easily mislead ourselves into believing that we are following a structured process by sitting through presentations about each option, evaluated in its entirety, with pros and cons, followed by a decision making or voting meeting. This method is subject to precisely the same biases - confirmation bias for things you like, and recency bias for the last option presented. It is essentially the equivalent of a holistic gut call.

Here is the MAP alternative:

- Agree upfront on what the goals are. To continue with our example, let’s say the objectives are 1) increase the number of daily users, 2) improve the performance of the app, and 3) reduce our operational costs.

- One presentation per goal. This method allows us to compare all proposals, on a particular dimension, instead of looking at all the aspects of one proposal. If we have a scoring rubric, we can score proposals per goal at this stage. These assessments are called mediating assessments.

- A final evaluation of all proposals, while looking at the mediating assessments. Note: we are not merely taking a weighted average of the intermediate scores. Instead, we are using our judgment at this juncture while keeping all the data in front of our eyes.

The changes seem subtle, but the impact can be profound. The best proof of this approach is in the use of a structured interviewing process to evaluate candidates. If you have interviewed at modern tech companies, like Facebook, Google, or most modern startups, you have experienced this. Instead of having each interviewer simply provide an overall score, the interview process involves a series of mediating assessments.

In structured interviewing processes, each person interviews and makes a judgment about one area of competency - coding, system design, communication, people management, etc. Interviewers score candidates per dimension. The hiring committee looks at all the intermediate scores and then determines an overall rating. This approach is different from each interviewer judging the candidate in all of the different areas and giving one overall score. Structured interviewing is the norm in almost all tech companies. Studies on personnel selection have conclusively shown that using such approaches to interviewing leads to more accurate long term outcomes.

Framework 3: WRAP#

This framework is a summary of the WRAP process outlined in the Heath Brothers’ fabulous book Decisive. I strongly encourage you to read the book, as well as use the summary resources on their website (free registration required.)

The WRAP framework focuses on avoiding or overcoming cognitive biases that creep into all human thinking. It is easy to understand and practical to apply. Each maxim can be used independently toward decision making; apply a few or all.

1. Widen the frame#

Let’s go back to the car-buying example. We are trying to choose between a minivan or a Prius. This problem statement implies a particular frame: we have to decide between A and B.

However, the car is a means to an end - commuting to work, transporting children to school, picking up groceries, or traveling for leisure. In our choice, did we consider solving the more significant problem using some other means? Do we need a car at all? Could we use an electric bike to commute? Or Instacart for all groceries? How would that change our set of options?

A narrow frame is a common decision-making trap. It focuses our thinking on available options, instead of opening our minds to all possibilities, some of which may solve the problem in unique or non-traditional ways.

A classic sign of this trap is the “whether or not” question. When you hear your friend ask you “whether or not they should quit their job” or “whether or not they should build a feature” or “whether or not they should buy an iPad,” you should smell a trap. One way out of this trap is removing the option you are leaning toward and making that a non-option. What if you absolutely could not quit your job or buy the iPad? What would you do then?

2. Reality Test Your Assumptions#

When we survey the set of available options, we build models in our head of how those options are going to work out. These models get tested when they meet reality, and usually don’t survive. We try to improve our models by finding evidence that supports or disproves the model. However, because of confirmation bias, we are much more likely to seek validating proof, rather than the contrary, or disconfirming evidence.

One way to get around this pernicious problem is to look for opposing or disconfirming evidence. Imagine we are in love with a particular feature. Instead of looking for reasons to support our instinct, look for the holes in our reasoning. Why could this feature fail or underperform?

How do other similar features perform? This line of questioning helps us determine the base rate. If most similar features underperform (low base rate), it is unlikely that this particular one is going to be the breakout.

Looking for disconfirming evidence can be difficult, especially when we’re already heavily biased toward pursuing a particular path. One trick is to do a joint “premortem” exercise. Get together in a room, and imagine that you’re six months into the future. The feature has been built and launched and isn’t doing well. What went wrong?

Another approach to reality testing assumptions is to dip a toe in without diving in all the way. In the car buying example, we could rent a minivan for a week, followed by renting another car for a week, to test out what it would feel like living with that car. The cost of a mistake (perhaps you hate the way the minivan drives or turns out that the sedan is entirely too small for your family) is tiny compared to buying the car and discovering you made a mistake.

3. Attain Distance#

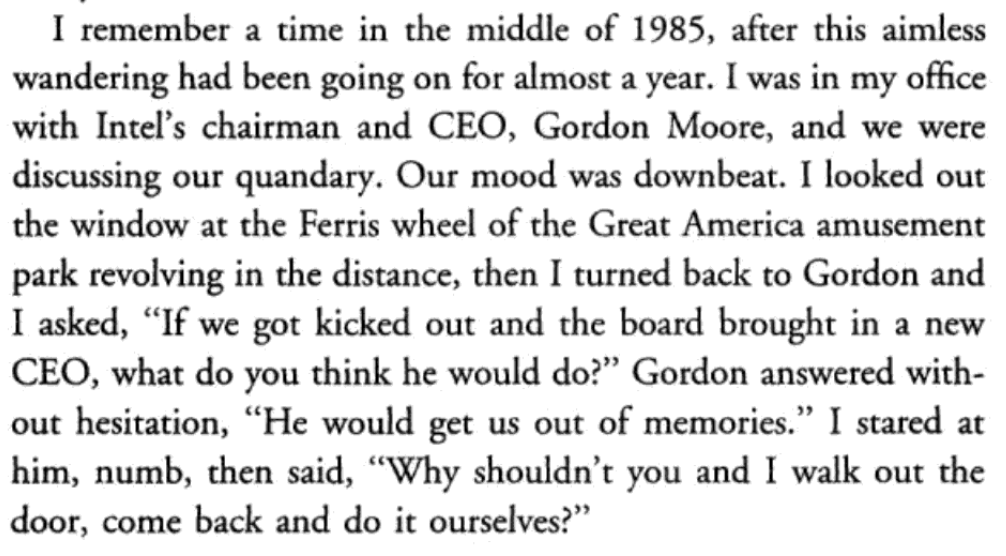

One of the most striking passages in Andy Grove’s book “Only The Paranoid Survive” is about Intel’s decision to pivot from making computer memory to making microprocessors. Intel started as a memory company - and they were the world leader in manufacturing memory chips in the late 70s through the early 80s. The microprocessor business was niche, dwarfed by the massive memory business. However, the memory business was seeing enormous pressure from Japanese manufacturers and steadily losing margin. Pivoting the company from their roots, to go all-in on microprocessors was an incredibly difficult decision. Grove described how they finally did it:

— via Google Book Search

For complicated psychological reasons, we seem to make clearer decisions when we are deciding for others instead of ourselves. One of the most effective techniques for attaining distance is to ask:

“What would you tell your best friend to do in the same situation?” — Personal Context

“If you were let go and we hired someone else, what would they do in the same situation?” — Professional Context

4. Prepare To Be Wrong#

We typically overestimate the impact of any particular decision. In reality, most decisions are reversible, or at least have escape hatches that are less catastrophic than we initially believe them to be. Jeff Bezos summarizes the concept of reversibility:

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions. But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

— Jeff Bezos, Amazon Annual Shareholder Letter

What if we made a wrong car-buying decision? We own a car that we don’t like, which we need to sell subsequently, and buy another car. There is a quantifiable dollar cost and some hassle in selling and buying cars and filing paperwork. But that’s it. With that understanding, we no longer fear making a decision, knowing that the cost of reversing that decision is not life-altering.

In Conclusion#

Life is full of decisions. In the majority of cases, our instinct is a great decision-maker. However, when faced with highly complex decisions, the evolutionary processes that helped us survive the lions on the savannah can mislead us into making poor, often irrational choices. Using frameworks to make such complex decisions allows us to counter some of those cognitive biases and make good long term choices.