Deliberate Practice (Feedback 2)

This is the second of three notes on Feedback. The first one covered pragmatic tips on delivering constructive feedback; this note goes into the theory behind achieving peak performance.

How do we become experts? How can we learn new skills in depth? What is the process, what are the steps, and who do we need? Deliberate Practice is one way to learn and grow: have clear goals, focus, get feedback, and overcome frustration.

– Photo by Jasper van der Meij on Unsplash

– Photo by Jasper van der Meij on Unsplash

I have been playing squash off and on for many years. Some friends got me into it, and I got hooked. It’s easy to get started, a fantastic cardio workout, and immensely fun. However, my game wasn’t particularly good, and I belonged in the lowest tiers of the club. Starting last year, I started getting coaching. During each session, my coach would point out three things to focus on, work with me on those three things, and then ask me to practice those things in solo practice over the week, before coming back to the next coaching session — the result: more improvement in 3 months than ten years of playing the game.

– Nour El Tayeb vs Raneed El Welily, Netsuite Open Finals, San Francisco, 2019

– Nour El Tayeb vs Raneed El Welily, Netsuite Open Finals, San Francisco, 2019

This story is not surprising for anyone that has seriously pursued sports, or music, or art: I got some coaching, and my game improved. Where’s the story?

Sports stories are interesting because people are engaging in Deliberate Practice without explicitly trying. Deliberate Practice is a theory by Anders Ericsson, described in his book Peak (YouTube summary video).

“Most individuals who start as active professionals or as beginners in a domain change their behavior and increase their performance for a limited time until they reach an acceptable level. Beyond this point, however, further improvements appear to be unpredictable, and the number of years of work and leisure experience in a domain is a poor predictor of attained performance (Ericsson & Lehmann, 1996). Hence, continued improvements (changes) in achievement are not automatic consequences of more experience, and in those domains where performance consistently increases aspiring experts seek out particular kinds of experience, that is deliberate practice (Ericsson, Krampe & Tesch-Römer, 1993)–activities designed, typically by a teacher, for the sole purpose of effectively improving specific aspects of an individual’s performance.

– Anders Ericsson, https://psy.fsu.edu/faculty/ericssonk/ericsson.exp.perf.html

In other words, it is easy to get started. Most people then hit a wall. Getting over that wall takes effort, focus, feedback, and grit. This formula applies to any learning activity and is how people become experts.

10000 Hours

Remember Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell’s 2008 book that shot up the NY Times’s bestseller list? He examined what factors differentiated the great people from the merely accomplished. He repeatedly brought up the concept of 10000 hours - the amount of time that experts dedicated to their craft, vs. about 2000 hours for amateurs.

Over time, we took this idea and ran with it - to be good at anything, we need to put in 10000 hours of work. In other words, put in this much work, and voila - you’re an expert. It turns out this isn’t true, and there are other factors besides the time that goes into building real expertise.

10000 Hours Of Deliberate Practice

What is “Deliberate Practice”? Ericsson breaks this down into four things:

- 🎯 Specific goal.

- 🕯 Intense focus.

- ⏱ Immediate feedback.

- 😢 Discomfort.

The best illustration of these is through the experiment that Ericsson’s research group ran, as described in Peak.

A graduate student is committed to spending an hour a week, working on getting better at a simple task: take a string of 7 random numbers, memorize them, and recite them from memory. They started at seven because that’s widely believed to be the number that humans can remember easily. When the student could quote them accurately, they increased the length of the number string (8, 9, 10 ..), and when they made a mistake, they reduced the series.

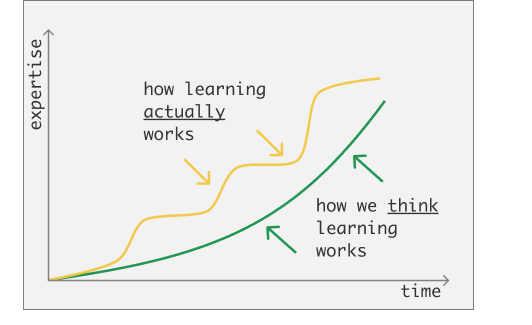

The student struggled with this for a while. It got frustrating. Then he made a breakthrough! He got to 11 digits. Then - frustration again. Struggle → Breakthrough! 22 digits! This pattern kept repeating itself till he got to 82 digits! 82 is an insane number of digits to memorize, and the student got there over the course of 200 sessions of an hour each.

Looking at this example through the lens of deliberate practice:

- 🎯 Specific goal: remember and recite strings of digits of increasing length.

- 🕯 Intense focus: no interruptions during the hour-long session, with a singular focus on the task at hand.

- ⏱ Immediate feedback: when he slipped, the string shrank.

- 😢 Discomfort: it was hard and frustrating.

Then they went one step further: they trained another student in the same task, but the first student was their coach and taught them his techniques in digit memorization. Result: the second student learned even faster and developed their techniques when the coach’s methods no longer worked for them.

Deliberate Practice At Work

Whether you’re an engineer, a designer, a data scientist, or a manager, you’re trying to be better at your job. There is a degree of intrinsic satisfaction in a job done well; there is a feeling of growth as you conquer and solve previously unsolvable problems. There are the extrinsic benefits of growth: bonuses and promotions, to go along with increased responsibility.

The best way to get better at what you do is to apply the principles of Deliberate Practice to whatever you want to get better at. Imagine you’re an engineer, looking to get better at your craft. What should you do?

- 🎯 Set a clear, measurable goal. It’s not enough to build a system; the system should have some performance or scale or other criteria that are hard to hit.

- 🕯 Focus. The modern, open workplace makes this challenging, but you can focus. Buy some noise-canceling headphones, clear your calendar, find a quiet room.

- ⏱ Get feedback. Engineering systems have intrinsic feedback built-in, via compilers, unit-tests, and end-to-end tests. Get human feedback through code reviews and design reviews, with people who are better than you. Managers can provide non-technical feedback, helping you pick the right problem, and communicate solutions.

- 😢 Be one with the discomfort. It won’t be easy. There will be days or weeks of no progress. Learning and growth have plateaus, and that is okay.

The Manager’s Role

What about managers? Managers are both coaches that are helping their reports, and humans who are improving their management skills. The best thing you can do for your team as their manager is to make sure they are adhering to the principles of deliberate practice:

- 🎯 Make sure everyone has clear goals. The weekly 1-1 is an excellent time to check in. Goals should form the beginning of every performance review conversation.

- 🕯 Defend their time. Focus is important.

- Block “maker time” on everyone’s calendars.

- Move all team meetings to a couple of days in the week, and keep the rest of the days blocked off for work.

- Encourage reading email twice a day and shutting down slack notifications a few hours at a time.

- Buy your team good, noise-canceling headphones. Bose QC-35-ii is my favorite. $250 here will be repaid in growth and productivity quickly.

- ⏱ Give them timely feedback. Giving good constructive feedback is hard, but crucial to growth. I’ve documented my thoughts and tips on how to give good feedback here.

- 😢 Be patient. Know that learning is not a smooth linear curve. It goes in spurts. Be patient when they are struggling with a plateau, knowing that if they put the effort in, the growth will happen.

Sidebar: Why does Peloton work?

I was a Peloton skeptic, and late to the party. It’s an incredibly expensive exercise bike, and I figured it was a craze. I could not have been more wrong.

The magic of Peloton is not about bikes being well built, or the instructors being amazing (they are), or the social pressure of leaderboards (it can be fun at times). Peloton is magical because it tricks you into deliberate practice without realization. Pelotons have:

- 🎯 Goals. You can set your own - get on the bike every day, compete with others, compete against yourself - all of these are easily trackable through the app.

- 🕯 Focus. It is impossible to do anything while you’re in a class.

- ⏱ Instant feedback. Your cadence, your resistance, your output.

- 😢 Pain. Thirty minutes into a 45-minute class, all you can think of is giving up.

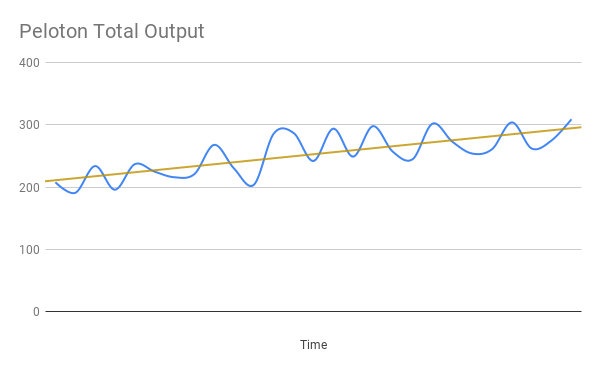

But it works. Here’s my total output over time for 30-minute intense efforts as evidence.

Tricking people into Deliberate Practice is something that a run-of-the-mill exercise bike cannot do. You can be on your exercise bike for 10000 hours vs a Peloton for a fraction of the time, and I guarantee faster progress toward your fitness goals on the latter.

Recap: The Feedback Series

This is the second of three notes on Feedback. We went into the theory of deliberate practice, which provides some hints on how to become an expert at anything.

- Delivering Critical Feedback

- Be timely. The effectiveness of feedback decays rapidly over time.

- Be firm and kind. Don’t beat around the bush, don’t sugar coat, and don’t be an asshole.

- Show the way. Point out flaws, but illustrate solutions with examples.

- Deliberate Practice 👈🏽this note.

- Have a specific goal.

- Focus on achieving that goal.

- Get rapid feedback.

- Persevere through the pain.

- Coaching

{% include about.md %}